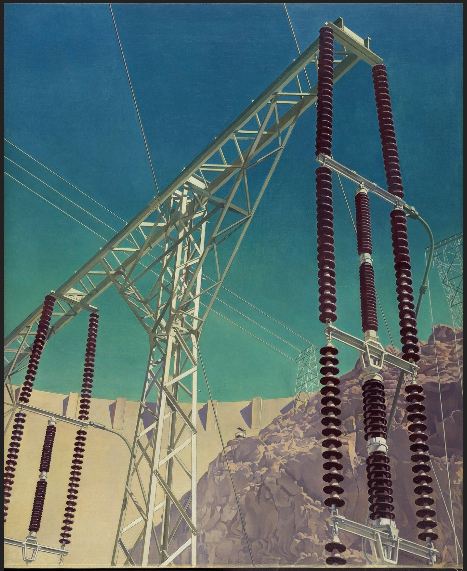

I find it hard to believe that I haven’t mentioned the work of Charles Sheeler here, outside of a mention of his collaboration with Paul Strand on the film Manhatta, a landmark American art film from 1921. Sheeler (1883-1965) is one of my favorite artists who as a pioneer in photography and painting in the early decades of the 20th century is often called the father of Modernism. Oddly enough, I am particularly drawn to his industrial imagery which replaces almost all evidence of things natural in completely man-made factoryscapes. This might seem to be the antithesis of my own work, which often omits all evidence of human intervention in my landscapes.

I find it hard to believe that I haven’t mentioned the work of Charles Sheeler here, outside of a mention of his collaboration with Paul Strand on the film Manhatta, a landmark American art film from 1921. Sheeler (1883-1965) is one of my favorite artists who as a pioneer in photography and painting in the early decades of the 20th century is often called the father of Modernism. Oddly enough, I am particularly drawn to his industrial imagery which replaces almost all evidence of things natural in completely man-made factoryscapes. This might seem to be the antithesis of my own work, which often omits all evidence of human intervention in my landscapes.

Some of his most potent work came from an assignment where Henry Ford hired Sheeler to photograph his factories, wanting him to glorify them in an almost religious manner, as though they were cathedrals for the new age. As Ford had said at the time, “The man who builds a factory builds a temple. The man who works there, worships there.” Sheeler was impressed with the factory complexes and felt that, indeed, they represented a modern form of religious expression. His painted work from this time glorified the machine of industry in glowing forms and color.

Some of his most potent work came from an assignment where Henry Ford hired Sheeler to photograph his factories, wanting him to glorify them in an almost religious manner, as though they were cathedrals for the new age. As Ford had said at the time, “The man who builds a factory builds a temple. The man who works there, worships there.” Sheeler was impressed with the factory complexes and felt that, indeed, they represented a modern form of religious expression. His painted work from this time glorified the machine of industry in glowing forms and color.

He saw the factory as a continuation of the American idea of work as religion, one that was rooted in the sense of reverence and importance of the barns and structures of the farms of the earlier pre-industrial age. He painted many scenes of farms and barns, abstracting the forms as he had with the factory scenes.

He saw the factory as a continuation of the American idea of work as religion, one that was rooted in the sense of reverence and importance of the barns and structures of the farms of the earlier pre-industrial age. He painted many scenes of farms and barns, abstracting the forms as he had with the factory scenes.

I don’t know that I completely agree with Sheeler on his idea of the factory as cathedral but I do have to admit to being awestruck in the presence of large factory structures. I remember working in the old A&P factory, a huge building that was said to have the capability to produce enough product each day to feed everyone east of the Mississippi. It no longer exists. Some of the huge rooms in the building were amazing to stand in, as the machines hummed and throbbed while workers hustled about servicing their needs. I particularly remember the tea room which was a huge ca cavernous space with row after row of steampunk looking machines that bagged the tea then sewed it shut. I cleaned these machines for several weeks and, standing in the grand space in silence after most of the workers had gone and the machines turned off, felt that feeling of awe. I would sometime walk around from area to area, just taking it in. I didn’t necessarily adore it in the manner of a religious zealot but there was no denying the power in its magnitude and the power of the machine.

I don’t know that I completely agree with Sheeler on his idea of the factory as cathedral but I do have to admit to being awestruck in the presence of large factory structures. I remember working in the old A&P factory, a huge building that was said to have the capability to produce enough product each day to feed everyone east of the Mississippi. It no longer exists. Some of the huge rooms in the building were amazing to stand in, as the machines hummed and throbbed while workers hustled about servicing their needs. I particularly remember the tea room which was a huge ca cavernous space with row after row of steampunk looking machines that bagged the tea then sewed it shut. I cleaned these machines for several weeks and, standing in the grand space in silence after most of the workers had gone and the machines turned off, felt that feeling of awe. I would sometime walk around from area to area, just taking it in. I didn’t necessarily adore it in the manner of a religious zealot but there was no denying the power in its magnitude and the power of the machine.

Maybe that’s why I’m drawn to Sheeler. Maybe its his use of form and color. I don’t know. I guess it doesn’t really matter. I just like his work. Period.