Since this is a busy morning, I was going to play a video of the paintings of a favorite artist of mine, Charles Sheeler. I thought I’d add a replay of a post from several years back that I wrote in case some of you were not familiar with his work. The video at the bottom features his work and Pamina’s Lament from the Mozart opera The Magic Flute.

I find it hard to believe that I haven’t mentioned the work of Charles Sheeler here, outside of a mention of his collaboration with Paul Strand on Manhatta, a landmark American art film from 1921. Sheeler (1883-1965) is one of my favorite artists who as a pioneer in photography and painting in the early decades of the 20th century is often called the father of Modernism. Oddly enough, I am particularly drawn to his industrial imagery which replaces almost all evidence of things natural in completely man-made factoryscapes. This might seem to be the antithesis of my own work, which often omits all evidence of human intervention in my landscapes.

I find it hard to believe that I haven’t mentioned the work of Charles Sheeler here, outside of a mention of his collaboration with Paul Strand on Manhatta, a landmark American art film from 1921. Sheeler (1883-1965) is one of my favorite artists who as a pioneer in photography and painting in the early decades of the 20th century is often called the father of Modernism. Oddly enough, I am particularly drawn to his industrial imagery which replaces almost all evidence of things natural in completely man-made factoryscapes. This might seem to be the antithesis of my own work, which often omits all evidence of human intervention in my landscapes.

Some of his most potent work came from an assignment where Henry Ford hired Sheeler to photograph his factories, wanting him to glorify them in an almost religious manner, as though they were cathedrals for the new age. As Ford had said at the time, “The man who builds a factory builds a temple. The man who works there, worships there.” Sheeler was impressed with the factory complexes and felt that, indeed, they represented a modern form of religious expression. His painted work from this time glorified the machine of industry in glowing forms and color.

Some of his most potent work came from an assignment where Henry Ford hired Sheeler to photograph his factories, wanting him to glorify them in an almost religious manner, as though they were cathedrals for the new age. As Ford had said at the time, “The man who builds a factory builds a temple. The man who works there, worships there.” Sheeler was impressed with the factory complexes and felt that, indeed, they represented a modern form of religious expression. His painted work from this time glorified the machine of industry in glowing forms and color.

He saw the factory as a continuation of the American idea of work as religion, one that was rooted in the sense of reverence and importance of the barns and structures of the farms of the earlier pre-industrial age. He painted many scenes of farms and barns, abstracting the forms as he had with the factory scenes.

He saw the factory as a continuation of the American idea of work as religion, one that was rooted in the sense of reverence and importance of the barns and structures of the farms of the earlier pre-industrial age. He painted many scenes of farms and barns, abstracting the forms as he had with the factory scenes.

I don’t know that I completely agree with Sheeler on his idea of the factory as cathedral but I do have to admit to being awestruck in the presence of large factory structures. I remember working in the old A&P factory, a huge building with a roof that was somewhere around 35 acres in size. It was said to have the capability to produce enough product each day to feed everyone east of the Mississippi. It no longer exists. A large shopping center now stands in its place.

I don’t know that I completely agree with Sheeler on his idea of the factory as cathedral but I do have to admit to being awestruck in the presence of large factory structures. I remember working in the old A&P factory, a huge building with a roof that was somewhere around 35 acres in size. It was said to have the capability to produce enough product each day to feed everyone east of the Mississippi. It no longer exists. A large shopping center now stands in its place.

Some of the huge rooms in the building were amazing to stand in, as the machines hummed and throbbed while workers hustled about servicing their needs. I particularly remember the tea room which was a huge cavernous space with row after row of steampunk looking machines from what looked to be the 1920’s that bagged the tea then sewed it shut. I cleaned these machines for several weeks and, standing in the grand space in silence after most of the workers had gone and the machines turned off, felt that feeling of awe. I would sometime walk around from area to area, just taking it in. I didn’t necessarily adore it in the manner of a religious zealot but there was no denying the power in its magnitude and the power of the machine.

Maybe that’s why I’m drawn to Sheeler. Maybe its his use of form and color. I don’t know. I guess it doesn’t really matter. I just like his work. Period.

Not knowing how near the truth is, we seek it far away.

Not knowing how near the truth is, we seek it far away. Again, I am busy this morning but want to share something from one of my favorites and an influence on my work, Grant Wood. I’ve written about his work here in the past, about how his treatment of his landscapes really affected the way in which I approached my own. There is always such a great rhythm and a beautiful harmony of color and forms in his work. They seem like living beings.

Again, I am busy this morning but want to share something from one of my favorites and an influence on my work, Grant Wood. I’ve written about his work here in the past, about how his treatment of his landscapes really affected the way in which I approached my own. There is always such a great rhythm and a beautiful harmony of color and forms in his work. They seem like living beings. The painting shown here on the right, Near Sundown, which was once owned by Katherine Hepburn, was a piece that really sparked me early on. The impression of it in my mind and memory still informs how I treat a lot of the elements in my own work.

The painting shown here on the right, Near Sundown, which was once owned by Katherine Hepburn, was a piece that really sparked me early on. The impression of it in my mind and memory still informs how I treat a lot of the elements in my own work.

I finished this new painting a couple of weeks ago and it has been a piece that I’ve spent a lot of time looking at since its completion. It satisfies me on many different levels and simply raises a certain contentment within me. I guess that would be the textbook definition of what I am trying to do for myself with my work.

I finished this new painting a couple of weeks ago and it has been a piece that I’ve spent a lot of time looking at since its completion. It satisfies me on many different levels and simply raises a certain contentment within me. I guess that would be the textbook definition of what I am trying to do for myself with my work. I’ve been very busy recently and haven’t had chance to write as fully as I would like. I’ve been doing this long enough that writing the blog has become habit and I feel a little guilty when I think I’m not attentive enough. But I have tried to alleviate some of my guilt by sharing some things that I do like. Like the video below of the work of Marc Chagall set to the music of Mozart’s Piano Concerto #23 Adagio.

I’ve been very busy recently and haven’t had chance to write as fully as I would like. I’ve been doing this long enough that writing the blog has become habit and I feel a little guilty when I think I’m not attentive enough. But I have tried to alleviate some of my guilt by sharing some things that I do like. Like the video below of the work of Marc Chagall set to the music of Mozart’s Piano Concerto #23 Adagio.

Scientific views end in awe and mystery, lost at the edge in uncertainty, but they appear to be so deep and so impressive that the theory that it is all arranged as a stage for God to watch man’s struggle for good and evil seems inadequate.

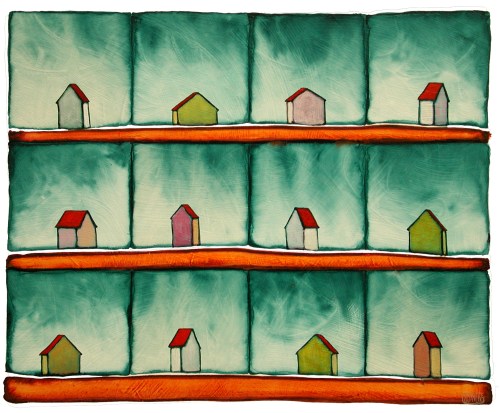

Scientific views end in awe and mystery, lost at the edge in uncertainty, but they appear to be so deep and so impressive that the theory that it is all arranged as a stage for God to watch man’s struggle for good and evil seems inadequate.  I was looking through some older images on my computer, searching for a painting that I had completed several years back. As I scanned through the paintings, I noticed several pieces through the years that were different from most of the work I’ve been doing recently. They were multiples, such as Peers, shown here. They were paintings with several windows with a new scene in each, although most of the scene were very similar to the others.

I was looking through some older images on my computer, searching for a painting that I had completed several years back. As I scanned through the paintings, I noticed several pieces through the years that were different from most of the work I’ve been doing recently. They were multiples, such as Peers, shown here. They were paintings with several windows with a new scene in each, although most of the scene were very similar to the others. I remember some of the early ones very well. One had 48 cells and had a great look, the result of overlaying the paint with layers of chalk and pastel. Another was the same number of cells with 48 individual small paintings, each window having a separate opening in the mat. It was a pretty difficult piece to mat and frame but it also popped off the wall. I will have to go through my slides from that time (pre-digital) and see if I can wrangle up a few shots. I would like to see them again to see how they really hold up against my memory.

I remember some of the early ones very well. One had 48 cells and had a great look, the result of overlaying the paint with layers of chalk and pastel. Another was the same number of cells with 48 individual small paintings, each window having a separate opening in the mat. It was a pretty difficult piece to mat and frame but it also popped off the wall. I will have to go through my slides from that time (pre-digital) and see if I can wrangle up a few shots. I would like to see them again to see how they really hold up against my memory.

I think I have seen this before but it caught my eye this morning. It’s a video of Turkish artist Garip Ay who works in the art of ebru, known to us as paper marbling. In this video he takes on Van Gogh’s Starry Night but that is only the start. What turns out in the end is a bit of a surprise although you may see it coming in the process. Just a neat video and a wonderful display of total craftmanship.

I think I have seen this before but it caught my eye this morning. It’s a video of Turkish artist Garip Ay who works in the art of ebru, known to us as paper marbling. In this video he takes on Van Gogh’s Starry Night but that is only the start. What turns out in the end is a bit of a surprise although you may see it coming in the process. Just a neat video and a wonderful display of total craftmanship.