Monde Parfait— At West End Gallery

Art is not a handicraft, it is the transmission of feeling the artist has experienced.

-Leo Tolstoy, What is Art? (1897)

When I first shared the quote above, I wasn’t sure if it was accurate or even from Tolstoy. I have found the source in the six of so years since it appeared here, and it was both from Tolstoy and accurate, appearing in an 1897 book titled What is Art? The book decried the elitist nature of art at the time when it was predominantly the domain of the powerful — the rulers, the ultrawealthy, the academies of higher learning, and the church– as well as the wealthy art dealers who chose what was suitable for these elite few.

The artists who thrived at that time catered solely to these few and were often richly rewarded for their efforts. They themselves became the elite.

In the chapter that contained the sentence at the top, Tolstoy foresaw a future where art would break free from such constraints and speak to all people, from most the common person to the most powerful among us. It was a peek forward at what the 20th century soon was to deliver us as it broke free from the entrenched traditions of art.

Art would become less academic, less constrained by rules. It would become a way of expressing emotions and feelings that sometimes were stifled in prior generations. Artists would no longer cater solely to the whims of the powerful but would aim to connect with the many. It would be art that would more accurately reflect the state of all people.

As the rest of the paragraph containing the sentence above states:

But art is not a handicraft; it is the transmission of feeling the artist has experienced. And sound feeling can only be engendered in a man when he is living on all its sides the life natural and proper to mankind. And therefore security of maintenance is a condition most harmful to an artist’s true productiveness, since it removes him from the condition natural to all men,—that of struggle with nature for the maintenance of both his own life and that of others,—and thus deprives him of opportunity and possibility to experience the most important and natural feelings of man. There is no position more injurious to an artist’s productiveness than that position of complete security and luxury in which artists usually live in our society.

Art must come from human beings with common human experiences and emotions. It must be a living thing derived from the richness of life as most people know.

In the blog post from several years back where I first shared Tolstoy’s words above, without knowing the full context, I wrote the following, which I think still applies:

Craftsmanship– handicraft– definitely has a part to play but that alone cannot transport the viewer to that inner spring from which their emotions flow. Something might be beautifully crafted but unless it is constructed from the empathy, the love, the awe, the wonder and the wide assortment of feelings that define our humanity, it remains just a lovely object. Beautiful but coolly devoid of feeling.

And there is nothing wrong with that.

But the aim of the artist, at least to my mind, should be to speak from their own emotions and experiences so that they can enmesh with the emotions of the viewer– or listener or reader, whatever their medium might be. To transmit and create a sort of communion of feeling between the artist and the recipient.

Can this be taught? I don’t know. I try to tell students to read, to look, to listen, to practice a sense of empathy in their daily lives. Widen their view and become a fuller person. I think art comes from an equal blend of one’s handicraft and their sense of humanity.

That’s just my opinion and it may be as flawed an idea as the mind that thinks it. But I can stand behind that thought and hope, in some small way, to achieve that blend in my own work.

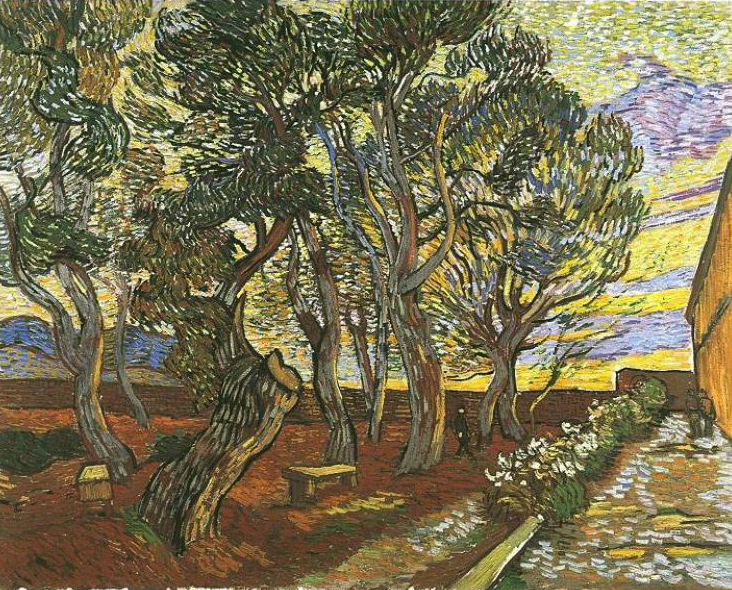

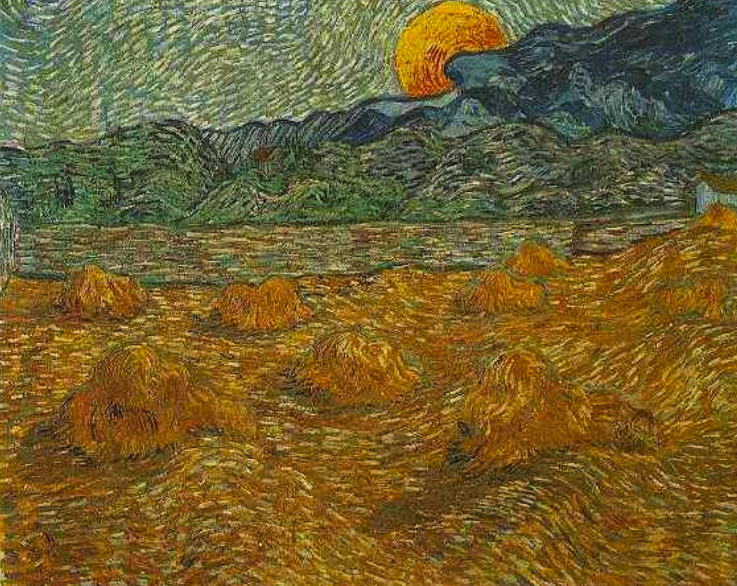

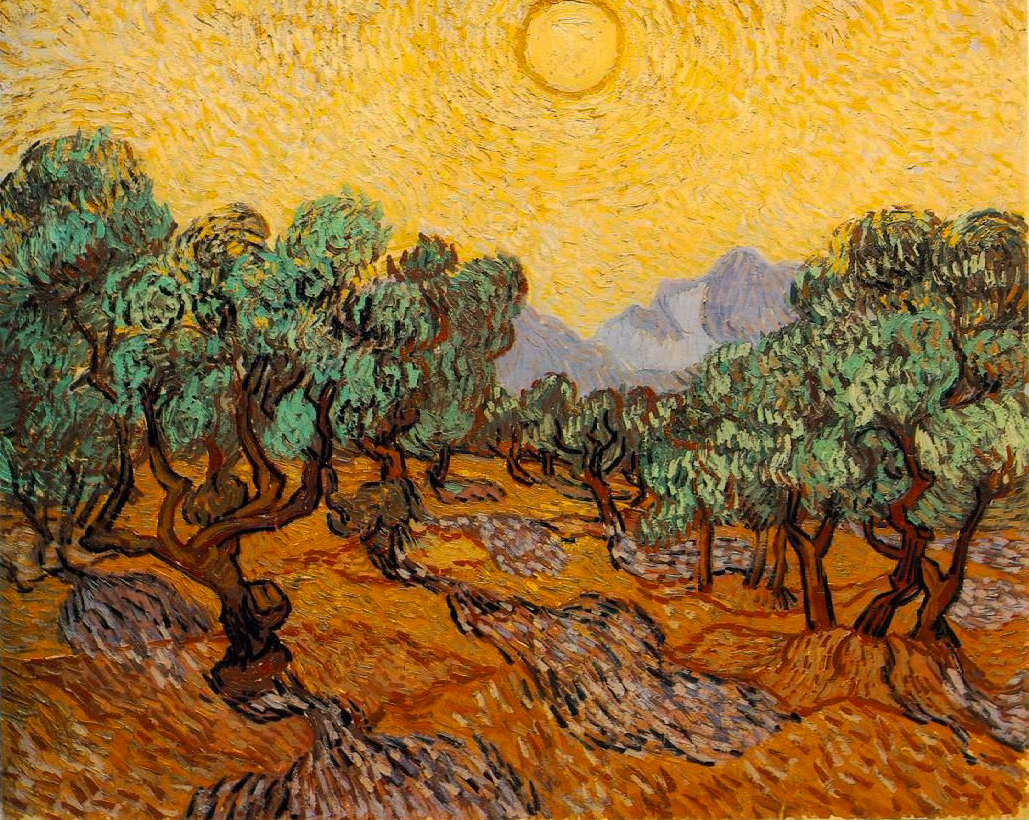

Of course, the future that Tolstoy foresaw was already on the move. For example, by the time Tolstoy wrote What is Art? Vincent van Gogh whose life and work very much represented what Tolstoy saw ahead., had been dead for several years. His influence and that of many other artists from that era had yet to change the art world — and the world in general. It was coming though. Here’s Don McLean‘s lovely paean to Vincent van Gogh, Vincent.

I showed this short video here about six years back, in 2010. It’s a compilation of morphing self portraits from Vincent Van Gogh put together by video maker Phillip Scott Johnson that I found intriguing then and now.

I showed this short video here about six years back, in 2010. It’s a compilation of morphing self portraits from Vincent Van Gogh put together by video maker Phillip Scott Johnson that I found intriguing then and now.